You may well be able to add rising health insurance premiums to the inevitable duo of death and taxes — especially if you live in central Pennsylvania.

Few Americans will escape the sticker shock of health insurance premiums. The rates are going up, especially for those who get coverage on the marketplace exchange. That’s in large part due to the growing likelihood that enhanced tax credits under the Affordable Care Act are about to expire.

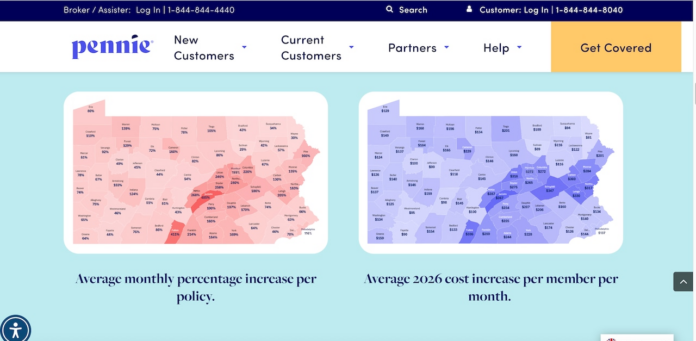

Across the central Pennsylvania region, though, the rate of increases outpaces the rest of the commonwealth. That’s true across all income and age brackets, but in particular, high earners in the 60+ age group, according to data from the health advocacy group, the Kaiser Family Foundation.

In some cases the price hike will be staggering.

Insurance shoppers in Dauphin County, for instance, would see a nearly a 200% average monthly increase without the enhanced subsidy, according to Pennie, the Commonwealth’s public insurance marketplace.

Two counties over, residents in Juniata County will see a 485% increase.

KFF, using federal data, gets even more granular: The average 40-year-old who earns $65,000 or more in central Pennsylvania and shops for insurance on the marketplace could see an increase of as much as $500 a month. Think small business owners and self-employed people.

A 60-year-old in that same income bracket would face a staggering $1,000 a month increase for premiums, compared to $500 elsewhere across the state.

“We’re trying to figure out what’s going on here in central Pennsylvania because we’ve seen with our payroll groups and group insurance some of the largest increases we’ve seen since I’ve been doing this,” said Fred Reeder, president of Lock Haven-based R&B Insurance Services.

“The older individuals seem to be the ones taking the largest hit.”

For anyone feeling a sense of comfort because they have private or workplace health insurance, brace for the reality check: As Reeder explained, premiums are going up across the board, even for so-called payroll programs, which include small businesses.

“It’s widespread,” he said. “It’s not just the individual market, it’s your groups also.”

Self-funded companies, Reeder explained, are likely to have some protection because they’re paying the claims and their stop-loss. Everything is based on their claims.

Everyone else seems to be in a panic mode.

“We are the busiest we’ve ever been with our phones ringing off the hooks where folks are just trying to find solutions for affordable health care,” Reeder said. “Right now they may be paying $200 to $300 for a plan, but if the subsidies go away, you’re talking $800 or $1,000 or more that they’d be paying for the same type of insurance.”

Reeder has in some cases already seen rates increase by as much as 78% for businesses.

“No business can absorb a 78% increase,” he said.

Pennsylvania is divided into nine “geographic rating areas.” Healthcare across central Pennsylvania tends to cost more than elsewhere, including the Pittsburgh and Philadelphia regions.

Factors contributing to that high rate include higher costs charged by hospitals, health systems, and physicians; a continuing post-pandemic surge in people seeking care and the pending expiration of the ACA tax credits in the personal marketplace.

Devon Trolley, executive director of Pennsylvania’s health insurance marketplace, Pennie, that serves some 500,000 people, notes that this year insurance customers will be hit with a double punch: the overall sticker price of coverage (the rates that insurance companies charge) and the premium tax credits under ACA, which help reduce the cost so that people don’t pay the full price.

The health of the population and the amount of healthcare needed can cause rates to go up, she explained. But when it comes to the subsidies, disparities among insurance plans have a lot to do with spiking rates.

“What’s often happening is some plans are going up a lot,” Trolley said. “And the benchmark plan, which is the plan that determines how much tax credit you get, is not going up as much. So it’s creating a gap.”

Benchmark plan gaps can help explain the sizeable disparities among Pennsylvania’s regions, on top of lower or non-existent premium subsidies.

“So normally the tax credits could keep pace,” Trolley said. “And sometimes you see those differences that the benchmark plan isn’t keeping pace even in a normal year.”

This year benchmark plans are not increasing as much as all the other plans and the premium tax credits are coming to a halt.

A region’s rating is dependent on a specific mix of the health plans in that area and the population in that area. An older population, which needs more medical care, can skew the price increase year over year.

The data suggests that rates in some areas across central Pennsylvania had been lower than average in prior years, Trolley said. Now they are catching up and getting closer to the average for the rest of Pennsylvania.

“So it’s more of a question of why were they lower in prior years? Which we have not really dug into,” Trolley said.

“Whatever has impacted other areas is now kind of impacting (central Pennsylvania regions) this year. But it’s also the year where the tax credits are going down so you have all these factors working together for really significant increases.”

Last year, for instance, the net monthly premium for people in the Juniata and Fulton counties region was the lowest in Pennsylvania — the average individual was paying under $100, compared with an expected average of $400 in the coming year.

Another factor is the cost of and demand for weight-loss drugs known as GLP-1s, with some simulations showing increases of 5% to 13% or more depending on factors like eligibility and drug cost, according to research by the AMA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

According to the latest KFF Health Tracking Poll, drugs like Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro and others taken by one in eight adults (12%). About half (54%) of all adults who have taken GLP-1 drugs say it was difficult to afford, including one in five (22%) who say it was “very difficult.”

Researchers found that from 2018 to 2023, spending on GLP-1s rose by more than 500%, from $13.7 billion to $71.7 billion.

“You’re seeing more GLP-1 drugs being prescribed for things other than diabetes,” Reeder said. “You’re talking like an Ozempic, which is a $1,200 to $1,500 prescription and somebody’s healthcare is $600 a month. The carrier is losing money on that. So the first thing they’re gonna do is try to recoup their premium dollars. When we’re working with larger groups that are doing self-funded, that is one of the biggest cost factors for larger companies.”

The idea that premiums are going up has met with pushback, particularly from Republican lawmakers.

U.S. Rep. Lloyd Smucker, a Lancaster County Republican, last week refuted what he said were the “overstated” effects of the expiration of enhanced premium tax credits on Pennsylvania consumers.

In a letter to Pennsylvania Insurance Department Commissioner Michael Humphreys, Smucker requested “full transparency” regarding estimated costs.

“The department’s claims about ‘skyrocketing’ premiums are misleading and paint a false picture for consumers,” wrote Smucker, whose 11th congressional district includes parts of York County.

Smucker argued that most Pennsylvanians will continue to qualify for affordable coverage and the average after-tax premium on HealthCare.gov for 2026 will be just $50 per month.

He claimed that 90% of enrollees will retain “a generous federal tax credit.”

Political rhetoric aside, the impact of all the head-spinning calculations on health insurance premiums is poised to hit hard.

Already, Pennie is monitoring changes in enrollment.

“Definitely in those central Pennsylvania areas where the increases are biggest, we’re definitely expecting a lot of sticker shock,” Trolley said. “And simply for that reason alone, because the increases are so big, we are anticipating that we’ll see quite a bit of coverage loss in those areas.”

Trolley said the public marketplace has already noticed enrollment declines.

“They might be going without,” she said. “They might be dropping coverage for now and seeing what happens with federal policy. We are hearing that a lot of people who call in are aware of why their premiums are going up, that it has to do with this federal policy that’s been under discussion. So a lot of people might just be waiting to see what happens. And if it comes more affordable, we’re hoping we can get the folks who dropped back in. If it doesn’t become more affordable, I doubt we’ll be able to do that.”

Reeder offers several pieces of advice to consumers:

Speak to a counselor: Especially a PENNIE certified counselor. They will help you find the proper coverage out of all the plans out there.

Consider cost-share health plans: Especially for people who are healthy. Plans like those offered by Christian Health Ministries, for instance, are an option. But he cautioned some of these programs have restrictions on pre-existing conditions.

“And then this is the big one,” Reeder said. “If the rates look too good to be true. They probably are.”

“There are a lot of companies out there that are saying, you can get health insurance for $110 a month or you can get this or that and you’re getting what you’re paying for. A lot of them are scams, A lot of them are so watered down, coverage may cover wellness type visits but then after that it’s not going to cover anything.”